'China was turned into a nation of opium addicts by the pernicious forces of imperialist trade'. Narcotic Culture: A History of Drugs in China systematically questioned this image on the basis of extensive primary sources, showing that opium had few harmful effects on either health or longevity, that most smokers used it in moderate quantities without any fatal 'loss of control', and that the substance was prepared and appreciated in highly complex rituals with inbuilt constraints on excessive use. In a culture of restraint, opium was an ideal social lubricant which was helpful in maintaining decorum and composure, while moderate smoking was a vector of male sociability and social inclusion. Opium was also a medical panacea before the availability of modern medications such as aspirin and penicillin: it allowed ordinary people to relieve the symptoms of dysentery, cholera, malaria and tuberculosis and to cope with pain, fatigue, hunger and cold.

If opium was medicine as much as recreation, Narcotic Culture also provides abundant evidence that the transition from a tolerated opium culture to a system of prohibition produced a cure which was far worse than the disease. Heroin and morphine were snorted, smoked, chewed or injected in the wake of the anti-opium movement, often in conditions which were far more harmful than opium smoking. Although heroin pills were smoked at all social levels in relatively small and innocuous quantities, some hardly containing any alkaloids at all, the dirty needles shared by the poor caused lethal septicemia and transmitted a range of contagious diseases: prohibition spawned social exclusion and human misery, engendering, however inadvertently, the very problems it was designed to contain.

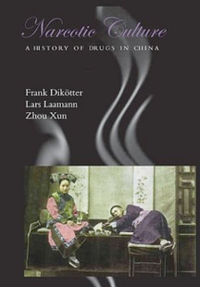

London: Hurst; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

For a sample click here.

For a review click here.