'What drives Frank Dikötter, chronicler of China’s insanity?’, The South China Morning Post, 15 June 2016

The first line in the preface to Mao’s Great Famine, by Frank Dikötter, states: Between 1958 and 1962, China descended into hell. He then goes on to describe it. By page 33, in the 420-page paperback edition, villagers in Gansu province are already referring to rural water-conservancy projects as “the killing fields”. That term is usually associated with the activities of the Khmer Rouge in mid-1970s Cambodia; but, years earlier, millions of people were dying in China’s countryside and cities.

Death came in various guises. Apart from straightforward starvation, there were accidents as exhausted novices grappled with the mechanics of the Great Leap Forward, inadvertent poisonings in collectivised canteens, beatings, hangings, burials of those still living and many, many suicides. Nor was death necessarily the end. Occasionally, corpses were dug up and eaten. In July 1962, Liu Shaoqi, China’s head of state, summoned Mao Zedong, the Chinese Communist Party chairman, to Beijing.

“So many people have died of hunger!” Liu told him and, he added, “History will judge you and me – even cannibalism will go into the books!” For Dikötter (whose book has, indeed, a chapter titled “Cannibalism”), it was the defining moment not of the famine – the Great Leap Forward had begun petering out early in 1962, after the deaths of at least 45 million people – but of Mao’s decision to get rid of Liu. That desire would trigger further mayhem.

The final words of Mao’s Great Famine, a book that went on to win the 2011 BBC Samuel Johnson Prize for Non-Fiction, are: “Mao was biding his time, but the patient groundwork for launching a Cultural Revolution that would tear the party and the country apart had already begun.”

Dikötter’s second volume, in what would turn out to be a trilogy on modern China, didn’t look ahead, however, but back. In The Tragedy of Liberation: A History of the Chinese Revolution 1945-1957, the new China under Mao’s leadership begins, as it clearly means to go on, with brutality, starvation, torture, beatings, suicides. Death quotas are handed down, inhumanity is rampant, millions suffer. That book was shortlisted for the George Orwell Prize.

Now, with the recent publication of the third book in the series, he has circled back to 1962 and the point at which Mao begins to plot Liu’s downfall. The Cultural Revolution: A People’s History 1962-1976 is, like its predecessors, studded with the kind of detail that lingers: the piles of shoes left after each rally in Tiananmen Square as the crowds surge forward to see Mao (afterwards, Dikötter writes, students “in flimsy socks could be seen poking around trying to retrieve a matching pair”); a family of seven with no clothes, wrapped in straw, the father sobbing in the corner; a brief aside, just as ping-pong diplomacy is beginning, that three of China’s best table-tennis players have committed suicide.

As a reader, you find yourself outraged, fascinated, overwhelmed. Language itself – left, right, red, black – shifts into senselessness. Eventually, armchair grappling with the relentless insanity of that era can do your head in. (A personal low point was reaching page 232, and a chapter headed “More Purges”.) For the past decade, Dikötter’s research in China’s archives has given him extraordinary insight into what was happening not just at the top, but at ground level. He’s had access to many personal accounts and reminiscences: he calls his overview of the People’s Republic of China the “People’s Trilogy”. What does such long-term immersion do to the head of such a writer?

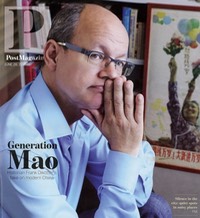

DIKÖTTER, 54, IS CHAIR PROFESSOR of humanities at the University of Hong Kong, which is where we meet one recent afternoon. His 10th-floor office in the new Centennial Campus has stunning views north, across the harbour. There’s a wall of bookcases devoted to China and some framed Great Leap Forward propaganda posters sit on the floor. A Penguin paperback of Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism is splayed, mid-read, on the arm of a chair.

We’d previously met on a couple of occasions. The first was at a dinner party about eight years ago, when he was working on the famine book.

“And you’d said, ‘You’re going to do that? But hasn’t Jasper Becker already done it?’” he remembers, cheerfully. In 1996, Becker (then the South China Morning Pos ’s Beijing bureau chief ) had written Hungry Ghosts: China’s Secret Famine, the first in-depth account in English of the hidden horrors that accompanied the Great Leap Forward.

The second time we’d met was by chance, in 2012, in an office building in Mody Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, where Dikötter – now garlanded with international accolades and lined up to speak at the Jaipur Literature Festival – had gone to get his Indian visa. He’d recalled the Becker conversation. I’d expressed mortified relief that he hadn’t paid any heed to it. But it turned out that he had: he’d gone back to Becker’s book and to his own source material to compare them, and to reassure himself that he had something new to say. He was (he said) glad I’d made the point. Clearly, he’s a gracious – and highly diligent – man.

For the first few minutes of this interview, however, he talks about another book – a slim volume in French, Douceur de l’aube (“softness of dawn”), by a man called Hervé Denès, who attended a recent Dikötter talk in Paris and gave it to him afterwards. In 1964, Denès was a teacher in Nanjing, where he’d met a young Chinese woman. They weren’t allowed to marry and he’d had to leave at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution. It took him a decade and a half to find out that the woman he loved, accused of having “foreign ties”, had jumped out of a building a year later.

“I felt gutted, gutted,” says Dikötter, who speaks with engaging passion. “It’s horrible. On page 89, the very last page, he finds out what happened to the love of his life. I almost cried.”

The story is one droplet in a tragic sea. As Dikötter says, he’s using it to make two points.

“The first is that history isn’t about numbers. It’s not about a theory, an approach – it’s about human beings and you must really bring it to life. And the second is that it’s real. It’s not just on paper. This Parisian guy has been living with this horrible feeling until now.”

But didn’t that urge to weep occur frequently?

“If you want to know the experience of being in the head of Frank Dikötter, here’s an example,” he says. “I remember one moment, in an archive in Hunan, within months of starting on Mao’s Great Famine. There’s a cadre, Xiong Dechang. He’s basically the local bully. He forces a man to bury his son alive for stealing a handful of grain. That turned my stomach. I read this. What do I do with it?”

His dilemma had nothing to do with covering up state-sanctioned excess; it was about deciding the level of horror he should present in a serious book. So he was concerned about torture-porn?

Dikötter hesitates for a second then says, “Yes. A term historians use is sensationalism or emotionalism. It’s used by men about women – for example, Cecil Woodham-Smith.”

Despite her first name, Woodham-Smith was female. In 1962 (as it happens), she wrote The Great Hunger: Ireland 1845-1849, a classic work about the Irish famine.

“She was criticised by historians for being too emotional. They said she should have buried that, she should have killed these people twice. It’s what Elie Wiesel [the writer and Nobel Peace Prize winner] says, ‘The executioner always kills twice, the second time through silence.’ I don’t want to be complicit.”

However, for the Cultural Revolution book, he says he has “a slightly lighter touch – I don’t want readers to think it’s Mao’s famine all over again”.

For each of the three books, he spent about six months gathering information in archives and about two years reading through primary sources. Then he wrote 1,000 words a day, five days a week.

In the beginning, he didn’t sleep well. “But you learn how to live with your work. It’s the topic I picked. And I realise the best cure to release it is to share it, to let it go.” Asked what he thinks about “trigger warnings” (i.e. alerts about potentially distressing material, currently a hot topic in academic circles and source of much media scorn), he replies, with cheerful exasperation, “At Princeton, six weeks ago, at a talk, someone asked me, ‘Why is it always unhappy stories?’”

"I HAD A WONDERFUL childhood.” From the age of seven, Dikötter, who is Dutch, lived in a village of 50 houses and three streets in the middle of the countryside. His father, an engineer, worked for Dutch State Mines (DSM). At night, the young Frank never closed his curtains because he liked seeing the flames’ glow from the works. When he was 12, the village was completely – deliberately – destroyed by DSM.

“We were the last household to move out,” he says.

The family relocated to Geneva, in Switzerland.

Many years later, in Taipei, he passed a hostel where he’d stayed as a foreign student in 1983. He told a friend he was with at the time that he’d have been deeply upset if the hostel had been demolished.

“My friend pointed out the connection and suggested that was why I was a historian. I’ve always been interested in things in the past.”

As a historian who wants to convey the past of both victim and perpetrator, he believes that what’s key isn’t sympathy – it’s empathy.

“People say, ‘Don’t you hate Mao?’ I don’t hate Mao, he’s never done anything to me. I try to feel what he feels, what Zhou Enlai feels. Let’s face it, if you’re a dictator, especially in a one-party state, the chances of dying in your bed are pretty slim. As a historian, your empathy should extend to every single person. That’s the art – juxtaposing one next to the other, seeing from both perspectives.”

When did he learn that?

He pauses. “Oh. That I don’t know.” After a while, he says, “Maybe, maybe this is going too far but … I moved a lot. We moved to the United States when I was five, and came back when I was seven. I spoke English, and I had to learn Dutch again.” The happy interlude in the now obliterated village followed. In Switzerland, at 12, he was sent to a French school. “In effect, I never truly felt part of a language or culture. The result of moving about is you had to watch other people.”

He studied Russian – he loves the literature, especially Dostoyevsky – and history at the University of Geneva. Chinese was “a mere afterthought”. (Asked how many languages he speaks, Dikötter says, “Not many, all badly” but perhaps this is scholastic self-deprecation. There can’t be too many people in the world who peruse archives in Chinese then carefully analyse – in English – the useful Russian distinction between liudoedstvo, literally “people eating”, and trupoedstvo, “corpse eating”.)

In 1985, he went to Nankai University, outside Tianjin, for a year and then Guangzhou. He’d already spent a month in Leningrad, in 1982.

“All these Sinological students from Cambridge, Leiden, Stanford – many of them lived in a fantasy world. One Dutch guy literally had to be shipped back to Holland because he couldn’t cope with the grim nature of China at the time. But I knew what grim was, the meaning of communism, the one-party state. So when I discovered you can buy a beer, walk around, speak to people … it was not too bad.”

His PhD, which became his book The Discourse of Race in Modern China, was written at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, where he met his wife, Gail Burrowes; and for the next 20 years he focused only on Chinese history between 1895 and 1949, because that’s the period for which research material was available.

“There wasn’t enough stuff about post-1949. I’m always interested in empirical evidence, and I didn’t think interviewing people in Hong Kong, reading People’s Daily and policy statements, was any good. If you enjoy factual evidence, you were unlikely to pick post-49 China except for ideological reasons.”

But one day in 2001, while he was researching pre-1949 prisons in a Shandong archive, he came across information on 1950s gulags. China’s archive law was changing (partly, Dikötter says, because of pressure from Chinese historians who could study China in archives of the former Soviet Union but not in their own country). From about 2004 onwards, it was possible to peer into relatively “soft” party records of life, and death, in communist China. In 2006, having been a visiting professor at HKU for the academic year of 2004/5, he and his wife moved to Hong Kong.

WHAT’S IT LIKE, SIFTING through those official reports, surveys, letters, statistics?

“It’s like – I hate the expression – shooting fish in a barrel. You must be very dim if you don’t find something interesting in a day. There is so much and it is so profoundly absorbing. It’s as close as you can get to time travel.”

I’d assumed that real-time travel across the border is difficult for him these days but he says not.

“Can I get a visa? Yes I can. I did go back to the archives when I started the Cultural Revolution book thinking, ‘They’re not going to let me in.’ But they did.”

The attack has come from Chinese academics (one from Shanghai, having done the rounds in China, gave a two-hour denunciatory talk in Hong Kong) and he’s received much hate mail of the “Go-back-to-your-Dutch-clogs-and-plant-tulips” variety. Early on, he’d noticed the curious fact that such e-mails tended to be sent on Sundays; a kindly journalist enlightened him to the existence of China’s weekend 50-centers (wumao), who earn that amount for each cyberbombardment of an assigned target.

Still, his fascination with authoritarianism continues. His next book will explore how dictators nurture the cult of personality to enhance power. He’s chosen eight: Benito Mussolini, Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Kim Il-sung, Mao, Francois Duvalier (of Haiti), Nicolae Ceausescu (of Romania) and Mengistu Haile Mariam (of Ethiopia).

“I’m not just interested in how they come up with their image. I’m interested in how they learn from each other.”

Making intergenerational links doesn’t seem to interest him quite so much. In the Cultural Revolution book, there are two references to Xi Zhongxun, a party elder who was purged. Dikötter makes no mention that this was President Xi Jinping’s father. Why not?

“Was it self-censorship?” he muses aloud. “Was it that I don’t want him in the index? It must have been a thought process … I must have thought, ‘I’m not going to mention it’s Xi Jinping’s papa. Or that Bo Yibo [another party elder, also fleetingly mentioned, also purged] was Bo Xilai’s papa.’”

Through every page of the book, through the flip-flopping of factions and the brutal severance of the most basic human bonds, you think: could this happen again? Dikötter is briskly pragmatic.

“So. Here we are in 1960 and people are very busy saying we must make sure the Holocaust never happens again. And then millions die. The awful thing is that it happens again and again. But it’s never going to be the same.”

His dictators book seems to be signalling a distinct shift away from China – Mengistu as get-out clause. Is he optimistic about Hong Kong?

“No, I’m not. You can feel it, that sense of relentless pressure on every little bit of freedom. Five people were punished at HKU for no good reason, without accountability or transparency.” But he treads carefully in any discussion of the consequences of Arthur Li Kwok-cheung’s appointment as HKU council chairman in January (although later, he says, more frankly, “It’s what you said, Mengistu is my escape.”)

And that’s the other point about the book: you constantly think, “What would I have done?”

“I’ve always been as apolitical as possible,” he says. “It’s always very nice to imagine yourself among the free and unfettered. But what would I do if I have to denounce my wife? We’re all s**ts … The capacity to be s***ty to each other in the right circumstances is unfathomable.”

All the way through a long, enjoyable interview one thing has been bothering me. For a man who has written so brilliantly, so empathetically, about its infernal consequences, those Great Leap Forward posters seem a Dikötter aberration. He says he bought them on weekends when China’s archives were closed, its flea markets were open, and he had nothing else to do.

“It’s propaganda,” he agrees, and he points to the blank wall above his desk. “This is why they’re not going up there. I’d like to sell them.” When I ask him to translate the characters above those smiling faces, stepping into their apparently shiny future, he can do so without hesitation.

“Let Us Get Organised,” he says. “Collectivised Life Is So Happy.”